The True Implications of Gang Databases

Gangs are often associated with violence, drugs, and crime, but there is a wide range of legal definitions for what constitutes a “gang.” These definitions often depend on jurisdiction. In some cases, as few as three people in a group can represent a gang. Other defining factors could include whether a group dresses similarly, uses hand signs or symbols, and locations where they hang out.

The Oklahoma definition for “criminal street gang” claims that a gang consists of five or more people who, as part of their duty to the group, participate in one or more crimes from a list of 18. It’s valuable to note that all 18 crimes listed are already considered illegal whether a person is part of a gang or not.

In today’s criminal legal system, those who have been associated with gangs, whether accurately or inaccurately, receive harsher punishments and longer sentences than they would otherwise be granted if they were not associated with a gang. These folks also experience greater adversity when it comes to accessing diversion programs. Gang databases are intended to improve public safety, but biases against those suspected of gang membership often prohibit individuals from accessing certain resources—deepening the cycles of oppression, racial profiling, and mass incarceration.

Preventing violence is important. However, we need to make sure we are taking the best approach to mitigate it while being cautious of stereotyping individuals. When we are focused on destructing and punishing gangs and gang members instead of tackling root causes of violence, we are choosing to punish social groups. This “tough on crime” focus distracts law enforcement and other criminal legal system stakeholders from protecting communities from harm.

Through this staff paper, we’ll unpack the implications of our criminal legal system’s approach when it comes to gangs. To get a well-informed understanding of how Oklahoma’s Criminal Legal System treats gang affiliation, we consulted with a variety of stakeholders. Perspectives came from current and former members of local police departments, the public defender’s office, a judge, the district attorney’s office, and an individual who has been involved with the system for decades. Each discussion brought informative and valuable insight into the overall picture.

Incorrectly listed as a gang member

According to accounts from individuals with lived experience, some people are mis-identified as members of gangs. When assumptions lead to documentation of inaccurate affiliations in gang databases, individuals and communities suffer. We talked with Chris, a Diversion Hub client, who shared a meaningful example of his experience which demonstrates the negative impact of mis documentation.

Chris graduated from Moore High School and got a full scholarship to North Eastern Oklahoma (NEO) to play football. NEO didn’t end up being a good fit for him, so he ended up transferring to Rose State. When he moved back to the metro, he often hung out at Will Rogers Courts, a public housing complex on the south side of Oklahoma City where it was common for people to drink and do drugs.

“It wasn’t the best area to hang around in Oklahoma City,” said Chris. “That’s when I got caught up with my first drug case. I was 22 or 23 at the time and was arrested and brought to jail. I bonded out but went back to the same situation and ended up back in jail again.”

Recently, he went to court and was informed that he’s documented as a gang member. “When you run with a certain type of people and they are gang-affiliated they associate you with that as well,” said Chris.

Even though he’s not a member of a gang, law enforcement marked him in the system, which has created significant negative outcomes.

“If someone didn’t know me and pulled up my paperwork, I wouldn’t blame them for thinking I was bad,” said Chris. “I look bad on paper, but that doesn’t reflect my character.”

Similar to Chris who found out in court that he was listed as gang-affiliated, there are likely others who have had their names entered into a database that don’t know that their information is there. Additionally, when and if an individual finds out they’ve been documented as a gang member, there is not a clear process to dispute the accuracy of the information.

Because of this inaccurate gang affiliation, Chris is unable to go to his kids’ sports practices and games, among other restrictions. He cares about his family and wants to show up and be a good father. Even though he’s never been violent, our criminal legal system is preventing him from being involved with his family and his community.

A national example of the injustices associated with gang documentation: The Bronx 120 Raid

While the Foundation’s work is focused in Oklahoma, this is a national issue that destroys families and disproportionately impacts Black and Brown communities. Let’s consider what happened several years ago in the Bronx of New York City. This example paints a clear picture of the injustices that result when our criminal legal system depends on gang documentation as a tool for crime reduction and prevention.

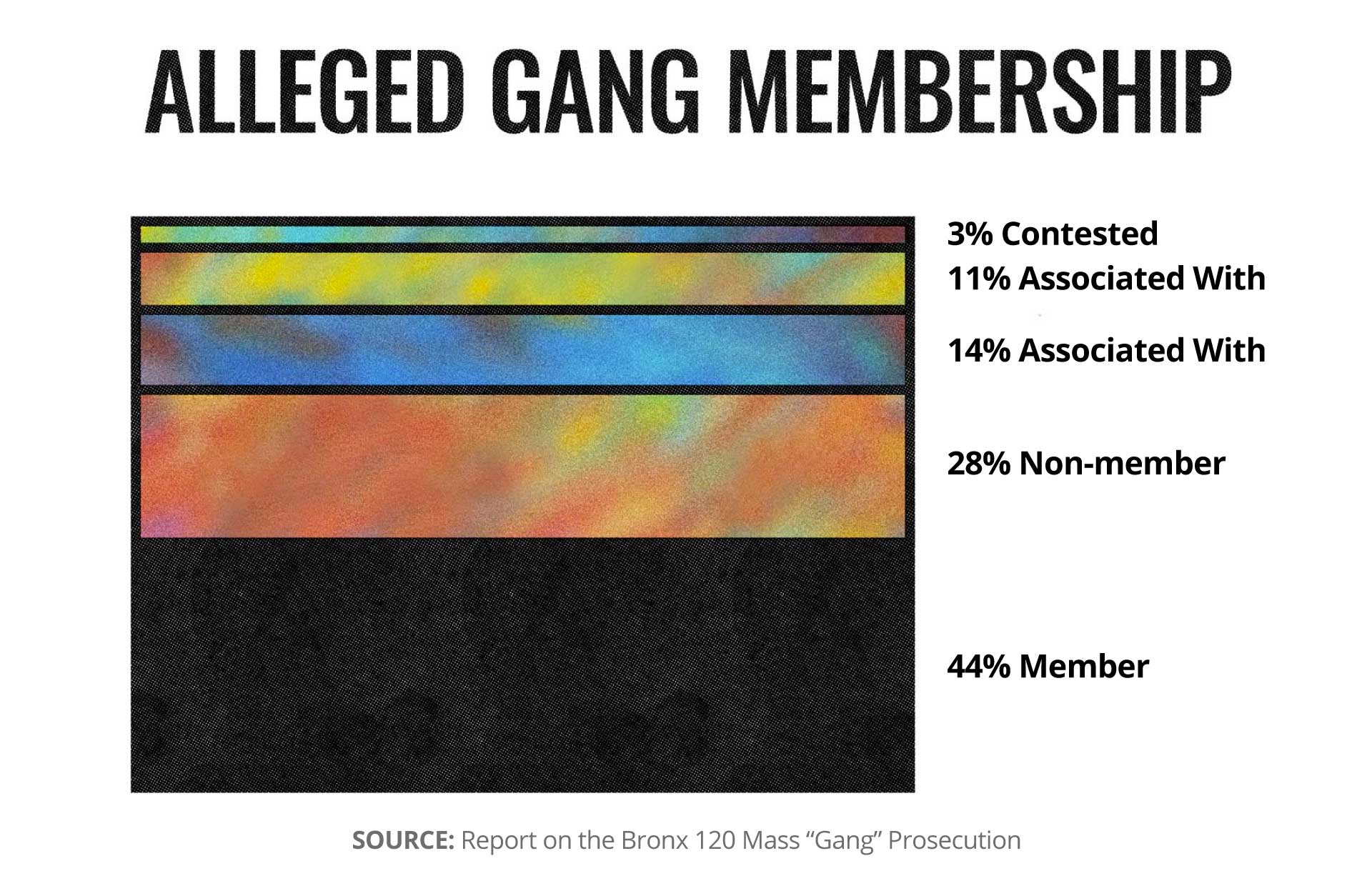

On April 27, 2016, 120 people, almost all young Black and Latino men, were charged in federal court based on gang membership documentation or affiliation with two rival gangs in the Bronx. Though the indictments included allegations of violence, none of the individuals targeted by the Bronx 120 Raid were charged with violent crimes. The broad inclusion of these allegations opened the door for bail being denied and increased the likelihood of harsher sentences, based on the gang associations—which were largely false.

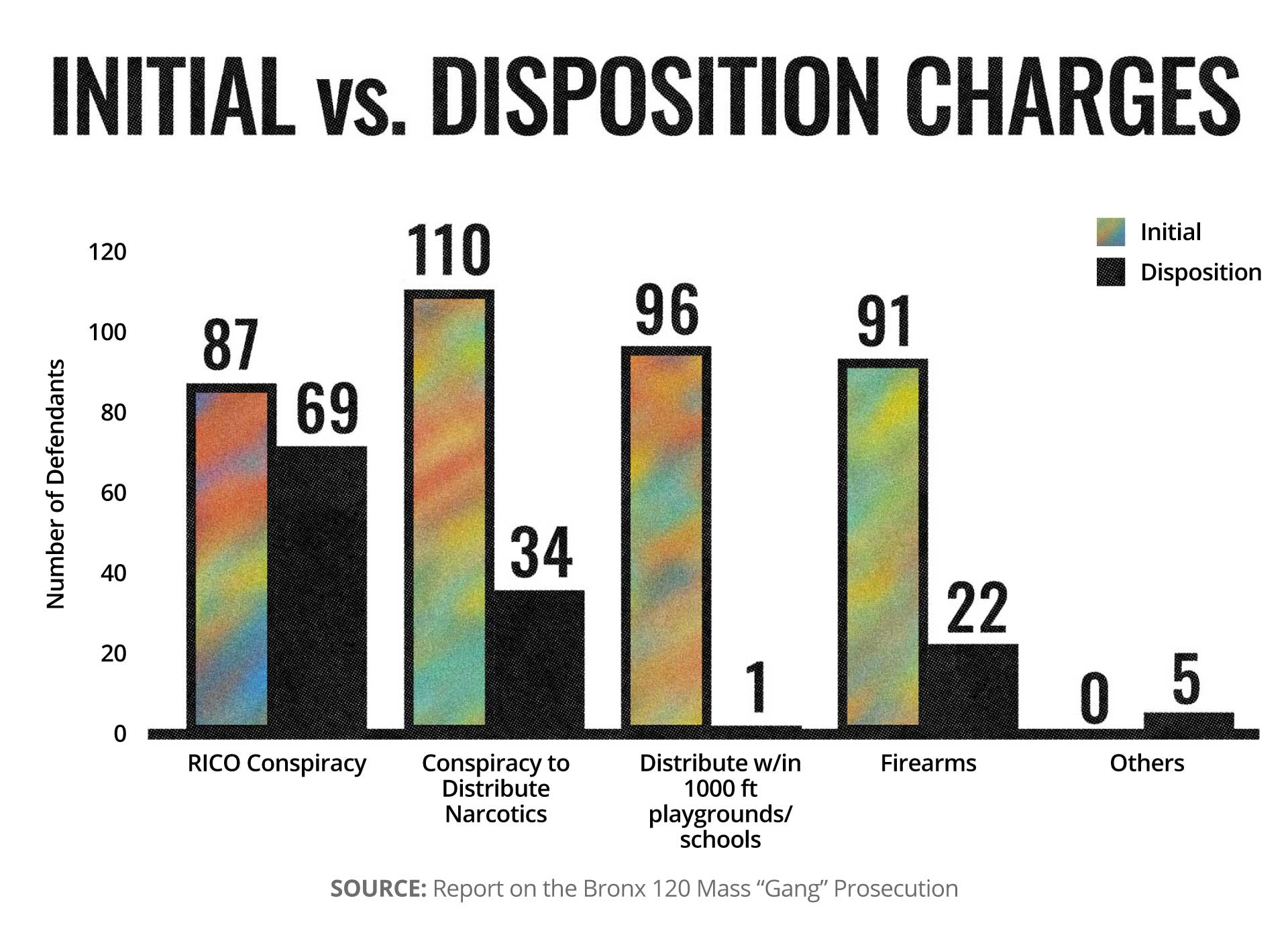

The chart below demonstrates the huge disparities between the charges defendants were arrested for and the outcome of their cases. As you can see, all of the initial charges (with the exception of the “other” category) were much higher initially than what individuals were found guilty of by law.

The raid in the Bronx required significant time and resources to conduct, and in the end two-thirds of the defendants were not convicted (https://bronx120.report/the-report/#thecharges) of any violence or firearm offenses. Additionally, many of the individuals tried for the more serious charges had already been prosecuted for them. At the time of the raid, many of the folks who were targeted for arrest were already in prison doing time for the same crimes law enforcement and political leaders claimed warranted the mass arrest.

While there is no consequence for a false documentation of gang membership, the potential negative impact on the accused can be astronomical. In this case, many who had either no prior criminal history or only low-level offenses were effectively forced into plea deals where they were required to plea to a felony. Even individuals who had already served time for related offenses were removed from their homes, families, jobs and communities for months following the raid.

In New York City, where gangs seem to be more prevalent than in the cities and towns of Oklahoma, less than 1 percent of crime is gang-related. With that low percentage, raids like the Bronx 120, do far more harm than good when considering the total impact of this mass approach.

Misconceptions and harmful assumptions

Some believe identifying possible gang members, giving them harsher punishments, and restricting their lifestyles will reduce crime. These tactics, however, have led to harmful outcomes for some of the most vulnerable communities and the assumption that a person’s proximity to a gang makes them part of one. These harmful assumptions are worsened with the belief that all gangs or gang members commit crimes.

Gangs form for a variety of reasons, often from a desire for belonging, safety, and support. Some gangs do have verified records of violence and organized efforts to break the law, but many act as social groups and aren’t inherently bad. Without excusing any real acts of violence performed by certain groups, it is important to consider the complexities of gang origins and reputations.

When we consider the complexities of these origins, we must also consider the historical context of racial profiling and injustices within the criminal legal system. And the remaining need for systems of and support for these communities.

Based on what we know to be true about the vast racial disparities in our criminal legal system/policing and arrests—we know these databases can turn a claim of gang membership into a digital stigma, subjecting people to unwanted surveillance and unwarranted law enforcement attention. These databases are used by law enforcement to manage, measure, and evaluate suspected gang activities. How the data is collected, used, and shared correlates with levels of racial inequality and other socioeconomic disadvantages reflected in American society.

What does Oklahoma’s approach to gangs look like?

To help us better understand, Oklahoma City Police Department (OKCPD) Lieutenant Stuart May helped shine a light on our community’s approach to gangs, starting from decades ago. May has been a police officer since 1983 and will be retiring in January of 2023.

“We started a gang enforcement unit in 1992. The gang unit was formed because of obvious issues we were having with gang activity in our neighborhoods,” May said. “The police department created a team of people who wore a special uniform of cargo pants and a pullover. It was a more subdued and practical uniform for doing the job that they were doing. Their cars were also marked with a ‘G.’”

Identifying individuals was subjective, and ironically, targeted people were often dressed similarly to the uniforms of the special unit.

“People in gangs were easy to spot back then,” May said, “they would gather in groups wearing similar colors.”

Others in law enforcement confirmed this process was similar throughout Oklahoma.

Dr. Stacey White, a retired Chief of Police and current professor of Criminal Justice Studies, said, “From my time as a patrol officer in 1991 at the Bixby Police Department, I can attest to the practice of collecting information on a possible gang member was as simple as having reasonable suspicion that the person we were in contact with was a gang member. Though we may not arrest them, we would pass their information on to a supervisor, and that person’s name would eventually end up on a hot sheet for gangs.”

Oklahoma’s police officers now have a few more guidelines in place for collecting information on gang members, but the process is still largely subjective.

Today, OKCPD officers no longer wear different uniforms or have specially marked cars. In 2020, shortly after Chief Wade Gourley took over for OKCPD, things changed for the department’s method in addressing gangs. What was previously known as the gang enforcement unit is now called the Violent Crime Apprehension Team.

“When someone is charged with a violent crime and a warrant is issued for their arrest, this team goes to pick these people up and bring them in,” said May.

Though OKCPD no longer includes “gang” in the name of the unit, the Violent Crime Apprehension Team seems to have the most direct contact and responsibility when it comes to addressing gang-related crime. On the Oklahoma City Police Department’s website, the team is described as:

“…responsible for the initial field investigation and suppression of violent crime throughout the city. The unit achieves its mission by responding to violent crime as it occurs, collecting evidence, conducting interviews, and arresting responsible parties. The Violent Crime Apprehension Team coordinates criminal investigations with local, state and federal law enforcement agencies and with other units of the Oklahoma City Police Department.”

Lieutenant May made it clear, “Being a gang member is not against the law.”

Though there is still room for improvement, the Oklahoma City Police Department has adjusted their practices to better support this truth. Police officers have a huge level of responsibility in determining who should be inputted into the database and shouldn’t take it lightly.

Where is gang-membership documented?

Gang information is entered into a database called the NCIC, which is the National Crime Information Center. Within their index, there are violent gang and terrorist offender files.

Below, are the criteria for Field Interview credibility. These requirements were found on the National Crime Information Center’s website.

Members of Violent Criminal Gangs: Individuals about whom investigation has developed sufficient information to establish membership in a particular violent criminal gang by either:

1. Self admission at the time of arrest or incarceration, or

2. Any two of the following criteria:

-

- Identified as a gang member by a reliable informant;

- Identified as a gang member by an informant whose information has been corroborated;

- Frequents a gang’s area, associates with known members, and/or affects gang dress, tattoos, or hand signals;

- Has been arrested multiple times with known gang members for offenses consistent with gang activity; or

- Self admission (other than at the time of arrest or incarceration).

According to Lieutenant May, “If someone admits that they are a gang member, an officer can fill out a gang F.I. (field interview) card. It goes to the police department, and the F.I. card is forwarded to the national database if they meet certain standards.”

How do you know if you’re in the gang database? Once you’re in, can you be removed?

If someone has no interaction with law enforcement for 5 years, their gang status can change to “inactive” within the database. But, according to the Oklahoma County district attorney’s office, even those marked as “inactive” in the system receive greater scrutiny when sentencing decisions are made. If you were once affiliated with a gang, there’s an assumption that you may still have a connection—even if you are 60+ years old and unable to get around without a wheelchair.

Because gang affiliation can prevent folks from getting into treatment programs and increase punitive measures taken against them with increased fines, fees, restrictions, and/or incarceration time, there is a huge need for law enforcement officials to understand the implications of putting someone into the system.

“It should not be a secret if you are in the database. You should be able to call a department and know if you are listed,” said Dr. White. “You should also have the ability to attest to have your name removed, and there should be an expungement protocol.”

Dr. White alludes to the fact that only law enforcement officials have access to the database where gang information is documented. The public defender can request this information, but it is not readily available. According to the public defender’s office, it’s possible for an attorney to advocate for a gang “stamp” to be removed from a person’s record if they are not an active gang member. However, the process is challenging and not always successful.

Oklahoma County district attorney’s office provides specific conditions for gang members on probation who enter plea agreements. The conditions explain that the defendant shall:

1. Not appear at any court proceeding unless they are a party or subpoenaed as a witness.

2. Refrain from any direct or indirect contact with the victim(s) or co-defendant(s) in the case.

3. Cooperate with law enforcement officers investigating any incident where they are a witness or victim.

4. Not be on any school campus, unless enrolled at the school.

5. Not be present at specified gang gathering locations identified by the district attorney or others.

6. Submit to search and seizure of person, property, automobile, residence or any container under their control at any time by any peace or probation officer.

7. Not make any gang-related social media posts.

There’s room for the district attorney to add any additional restrictions to the conditions agreement. If the defendant does not comply with the restrictions, they are subject to revocation or acceleration of the probated sentence.

Judges do their best to treat individuals equitably in their decision-making, but they must rely on the information that’s presented to them–and the restrictions associated with it. A combination of facts, law, politics, psychology, biases, and court processes all go into the decision. It’s not always clear if misinformation is being presented. To protect the application of the law and their own credibility, many judges must err on the side of caution, which reduces their ability to provide leniency for gang-marked individuals.

Dr. White’s concerns about the lack of transparency within our system hold special importance when considering those who, like Chris, are listed in the database but aren’t gang members. According to Dr. White, people have no way to confirm if it exists unless they hire an attorney and file for a subpoena. It has been discussed many times whether an intelligence or investigative database can be subject to an Open Records Act request. Allowing for these requests would reduce some barriers, offering a small step in the right direction.

What can we do moving forward?

There are multiple ways we can reduce the negative impact of gang database usage. Some of the obvious suggestions for change include:

1. Eliminate the gang databases entirely.One of the most transformative approaches is to get rid of it completely. Strong advocates for elimination of gang databases, like The Center for Popular Democracy and United We Dream argue that they are discriminatory, over-inclusive of people of color, and they have produced no evidence of reducing gang-related violence.

2. Reallocate law enforcement resources to community intervention programs. Money is often wasted on gang taskforces, and it could be better to reallocate that money into community intervention programs. Organizations like Live Free USA are doing this successfully across the nation.

3. Increase training for law enforcement officials. More substantive training of our law enforcement officials would help prevent misinformation from entering the system.

4. Make existing gang databases more transparent. If someone is marked as a gang member, they should be notified. The lack of transparency in today’s system lacks the protection of due process.

5. Create a clear process for disputing gang affiliation. Our criminal legal system should make it accessible for individuals to dispute false information regarding their identity. It’s unjust to allow for inaccurate affiliations to exist, as they have large influence on a person’s outcomes.

A key message when it comes to gangs and crime is that even though social groups may have positive or negative influences on an individual, poor choices are made by the individual themselves. Punishment should be directly related to the crimes committed, not based on the perception that someone is inherently “bad” because of the people they are surrounded by.

The utilization of gang databases is complicated, but if they aren’t going away, we must ensure their usage is more equitable and clear—for all parties involved.